Encounters with the Music of the Loom!

Samugheo: “saludi e trigu”, Health and Wheat!

The Bread & Wheat making tradition in Samugheo, Sardinia

Saludi e Trigu – Health and Wheat! What more could one hope for! The ancient Sardinian wish for prosperity in times of difficulty is born each day in the mills and bakeries of the island’s villages. Health requires food and the perfect food has always been bread.

The fundamental staple of life throughout the history of humanity, bread is a food sacred to all rituals – those of the home where we share meals with family, those of the community where we meet and eat in friendship, in celebration and in mourning, those of religions where the lives of our prophets are venerated and remembered by sharing bread. We ‘break bread’ to eat and because we are grateful to have it to sustain us.

On a recent cultural tour of Samugheo – a village in the hills of Sardegna – our small group was introduced to the artisans who mill the grains and bake the bread that feed the town and surrounding region. True to long-lived techniques held in the islanders’ collective memory but committed to the improvements brought by advances in science Bruno Sulis of Mulino Sulis and Antonello Meloni and Giovanna Frongia of Pane Nostu offered us fascinating narratives about the processes required to bring flour to the baker who then must transform it into bread for the hungry. Treated to demonstrations at each establishment, we saw first-hand the skills that turned grain into flour and flour into dough – and then bread – by hands and hearts guided by the inherited philosophy that continues to shape the way of life in the hills of Sardegna.

Bruno Sulis showing us his mechanized millstone machines and discussing the process of milling grain

Mulino Sulis different flours

Pane Nostu – freshly baked bread

The enthusiasm of miller Bruno Sulis, and husband and wife bakers Antonello Meloni and Giovanna Frongia was infectious! After witnessing the time and effort and care it takes to bring us quality products – the creation of which respects the health and needs of the land and the people – I will forever revere the experience with every loaf I bake and crust I eat!

Bread begins with wheat. In Samugheo, the seeds that grow the trigu – from which are milled the flours for pasta and bread – were born in the genius of Italian geneticists. Samughese farmers use five different organic seeds to produce their wheat – Senatore Cappelli – always the sole seed sown in a field – and a mixture of four other seeds – Creso – named for the famed Lydian king and which can be sown alone – and Pietrafitta, Saragolla and Karalis which are mixed together and that mixture used to sow the fields. These practices ensure a large and healthy crop every year no matter what travails the weather, plant disease, or any pest visits on the wheat fields.

Senatore Cappelli is a very special seed with a very interesting history. This wheat type was adopted in Italy in 1915 and named for the Italian Senator Raffaele Cappelli who championed it. Cappelli was developed by the renowned Italian geneticist Nazareno Strampelli (1866-1942). Strampelli participated in Benito Mussolini’s famous ‘Battle of the Wheat’ – the push to greatly increase Italy’s grain production without the need to claim more land for its cultivation – a necessary goal for a small nation with limited space and a growing population to feed. Strampelli was successful and his seeds increased the yield of the average Italian wheat field by 30%. By the inception of WWII more than 90% of Italy’s wheat was grown with his seed. Today, in Sardegna, 100% of the grain produced comes from Strampelli seed! His varieties of wheat seed are so prolific that they have been globally adopted and are preferred over all others in Italy! Italians rule wheat!

Mulino Sulis and Pane Nostu

The artisanal companies – Mulino Sulis and Pane Nostu – are both km-0 operations – kilometer-zero. In 1986 a famous Italian ‘foodie’ – Carlo Petrini – began a movement to preserve the distinct food traditions and products of the regions of Italy. His focus was on the freshness and authenticity of foods that were available for consumption in modern life – the frenetic pace of which undid the time and pleasure long associated with cooking and family meals in Italy. Pertini’s ‘Slow Food Movement‘ – the name an unambiguous response to the rapidly spreading fast-food phenomenon – was so successful that Time Magazine named him one of their 2004 Heroes of the Year! Because of Petrini, kilometer-zero became the sought after measure for food quality – native to a region and necessarily locally produced. A km-0 designation indicates that the products offered traveled no farther than one-hundred kilometers to reach the people who purchase them. Italy is dedicated to its farmers and committed to the goals of the Slow Food Movement as are the artisans of Mulino Sulis and Pane Nostu! Italy rules bread!

Our group began the day’s cultural tour by visiting a non-mechanized grain mill in the Samugheo countryside – Mulino di Giobbe. Here we saw how water alone could be the force that turned the stones that pulverized the trigu – hard durum wheat – turning it into soft powder – flour for bread and pasta. Power at the old mill comes from the forces of gravity – since the mill and milling apparatus sit low in the landscape – and the natural flow of the river, Rio Accoro, that fills a sluice which when opened results in a rush of water that turns the quartz millstones – quartz because that rock is immune to the heat normally produced by the friction of the spinning stones. Quartz millstones did not ‘cook’ the wheat kernels.

These water driven mills were the norm in Sardegna. A recent aerial analysis of the topography of the island showed evidence of 350 hydraulic factories – ancient and more recent grain mills – mulini – that relied solely on water to turn their millstones. Researchers pouring over the available historic sources of the towns and the antique maps of the villages confirmed the ownership and operation of 330 of those mills! Sardinians must have their daily bread!

To the present day reader this number may seem significant. But Abbot Matteo Madao (1733-1800) – a Jesuit friar and scholastic born in Ozieri – rued this small quantity in his 18th-century monograph on Sardinian history. As the Abbot opined in 1792: “…la Sardegna ha più di quattrocento mulini idraulici…l’isola ne potrebbero girare assai di più; se non fosse che i Sardi preferiscono le macine, le quali fanno miglior farina… “ (i.e. “… Sardinia has more than four hundred hydraulic mills…the island could produce much more; if it were not that the Sardinians prefer the millstones, which make better flour… “).

Yes – Sardinians must have their daily bread – but only if the wheat is ground between the stones of a water mill!

Mulino Sulis still uses millstones to grind the wheat – special stones called La Fertè that are quarried in the Jouarre Basin in France – but the power now comes from electricity. The process is lengthy – grain is fed into a multi-vat system where it is cleaned and washed – to remove the debris from the fields – and sifted to separate the kernels – the source of flour – from the husks – the source of bran. And the process is slow – the kernels are deliberately crushed and pulverized so as not to heat the wheat and ‘stress’ it. The result is a high protein flour that retains all its nutrients and can be used to make quality food stuffs.

Mulino di Giobbe

Mulino Sulis – the entrance to the mill

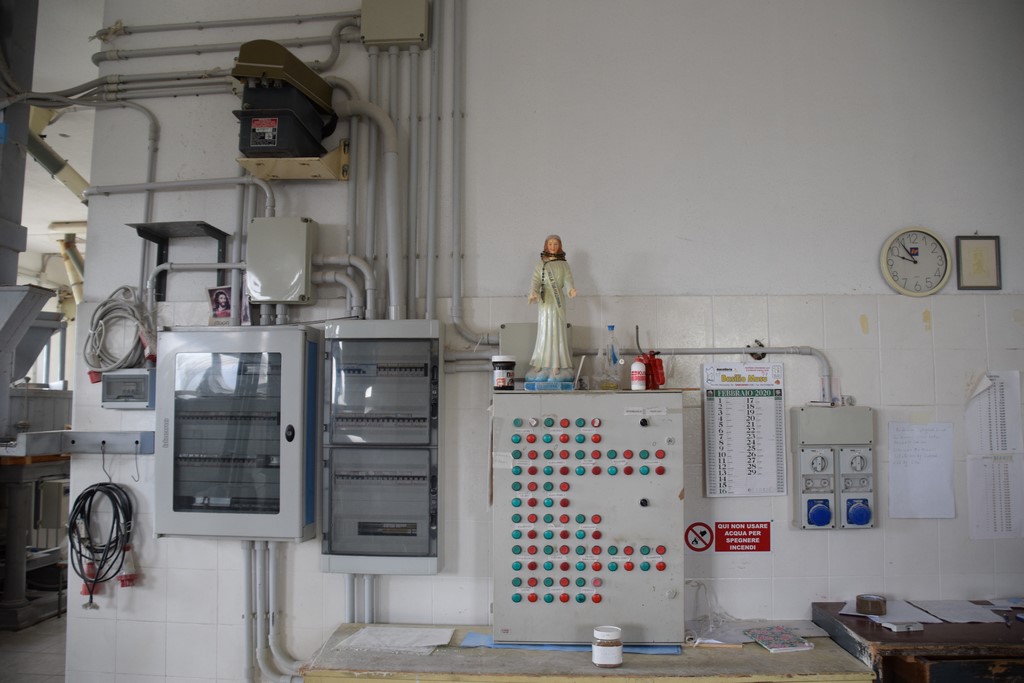

Mulino Sulis – the electrical controls which operate the millstones – all guarded by a statue of the Madonna wrapped in a rosary

Bruno Sulis put out small piles of the different flours he produces and we were able to touch them. The Trigu – durum wheat grain – was brown like the shell of a chestnut – and hard like small pebbles – making clear the reason such hard stones are needed to crush it. The Fiore Farina was pale yellow and felt silky and soft – perfectly suited for tender cakes and pastries. The Semola was lemon-colored and felt slightly gritty – like a fine corn meal. Semola – or semolina to Americans – is the highest protein flour and used alone or mixed with Fiore Farina to make different breads and pasta.

Mulino Sulis – The display of wheat berries and flour

Mulino Sulis – The Madonna watching over the mill and her owner

Pane Nostu – Topleft The colorful business card of Pane Nostu

After our visit to the mills we traveled a short distance to the panetteria – the bread bakery – Pane Nostu (i.e. “Our Bread” in Sardo – the Sardinian language). Here, Antonello Meloni and Giovanna Frongia make their unique Samughese bread three days every week – Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday. They, also, bake bread the day before all holidays – prefestivi! Adamantly controlling all steps in the bread-making process, the couple spends the other four days gathering the wood for their baking oven and working in the wheat fields to oversee the crop and ensure its successful harvest

I particularly enjoyed Giovanna’s discussion about the Mother Dough – the fermented bread-starter that must ripen for three weeks before it is hardy enough to make the new bread dough rise. All breads begin with her – the Madrighe – as she is called in Sardo. Every new batch of dough then lends a piece of itself to the old Mother Dough giving her a sort of eternal life born again and again in each loaf of bread. This thread of life – spun out from all who came before – weaves itself into the loaves of Pane Nostu – traditional breads of Sardegna made into the doughs and shapes native to Samugheo! What delicious romance!!

Pane Nostu uses a machine to mix the ingredients and begin the kneading process. Semola mixed and kneaded by hand takes hours. The coarse flour requires strong and tireless hands and arms for which a machine offers an effective and efficient exchange. When this process is complete, Antonello feeds the dough into what looks like a large, mechanized pasta machine which smooths, flattens, and stretches it.

Giovanna then cuts and shapes the different loaves by hand – snipping designs into the dough with small scissors. While the bread dough rises – covered and kept warm by clean, white cloth – Antonello readies the oven. The wood-fired oven is lined with a manufactured stone that absorbs moisture and evenly distributes the heat of the wood coals. I have such a stone in my oven – a flat piece on which I bake pizza and bread. Before the loaves are placed into the oven, the hearthstone must be washed and cleaned. For this Antonello uses a local plant – Cisto. Also known as a rockrose for its colorful flowers and preference for dry, rocky soils, the shrub grows weed-like in most Mediterranean countries. After the wood embers are moved off the baking stones, the Cisto – which is tied in a bundle onto a long wooden broomstick – is then dipped in water and used to wash the internal hearth.

Antonello fills the oven with wood, sets it alight, and then waits as the burning wood reduces to hot coals

Antonello has dipped the bundle of Cisto into a bucket of clean water and prepares to wash the hearthstone behind the smoldering wood coals

Giovanna Frongia shapes and snips the dough with her hands and scissors while Antonello Meloni carefully arranges the loaves on the cloth

When clean, the risen loaves are placed onto a wooden paddle – called a ‘peel’ – and slid into the oven. Soon the beautiful, browned bread is ready! After removing it, Antonello checked the bottoms of the loaves – deeming the hearth adequately clean enough to leave the baked bread free of any wood ash. Wonderfully pungent – the smell of the freshly baked bread further heightened our rapidly growing desire to taste it!

Antonello prepares to slide the risen loaves into the hearth. The bread is placed on the clean hearthstone behind the coals – deep inside

Antonello removes the hot bread from inside the oven while Giovanna watches

Giovanna Frongia slicing the freshly baked bread for us to sample

Giovanna sliced the first loaves and we retired to the front room to enjoy a lunch of local meats, silky Pecorino cheeses, and wines – all there to accompany the many different breads that Giovanna and Antonello baked for us. We ate until there was nothing left! How could we not! I have never had such delicious bread!

Before we left we were each presented with a gift of bread! Although I tried to save the loaves for my enjoyment when I returned to Milan – I was not successful. That bread called to me in a voice too loud to resist!

The different breads that are made at Pane Nostu which we were privileged to sample for our lunch

The remains of my lunch – salami, sweet prosciutto, freshly baked bread toasted and drizzled with olive oil, and locally produced wine – YUM

Our gift of bread from Antonello and Giovanna

Besides the generosity and devotion of the artisans who shared their passions, knowledge, and skills with our group – I have Italia Slow Tour to thank for these experiences – all led by our host Alessio Neri of Fare Digital Media and with fabulous simultaneous translations of the Italian provided for me by licensed Sardinian Tourist Guide – and polyglot – Elisabetta Arru! I have long been an amateur bread-baker – I really loved this day! Brava Samugheo! Grazie Mille Mulino di Giobbe, Mulino Sulis, and Pane Nostu! My heart and mind and stomach are full! I long to return to eat more bread!!

Virginia Louise Merlini

Thanks to Fare Digital Media, Samugheo Story and La Memoria Storica Soc. Coop.